Art Made by People (For People)

You might notice a new banner image on this site lately.

I originally had used an AI-generated image for the phrase "Cyberpunk Orthodoxy" (one I didn't generate myself but found online) since it was fitting given my interest in the weird intersection between religion, science, and technology.

After a while, I noticed this site's traffic on Google was being affected, and I suspected that the featuring an AI image so prominently might have depressed its reach (since Google has been trying to restrict the amount of AI spam that shows up in searches). I took it down, in part for traffic reasons, but also because I've become more morally opposed to the use of AI-generated content, even if it's somewhat ironic like my usage was.

For a while, I had left a NASA image of the Earth as a placeholder, but I was never satisfied with it since it felt rather generic.

That has changed recently, however.

I commissioned my friend D Moses (an artist and comic book writer who runs Pastitch Publishing) to hand-draw an image that would fit the themes and content of this site. I'm really happy with the final result: the striking image above, a priest with a mechanical hand holding up a communion chalice.

For one, I though it was important, given my conviction that we need to protect human art and creativity in an age of AI automation, to feature an image drawn by a real human being.

But I gave very few directives for this digital painting--the concept and image itself was designed and executed entirely by D, as an interpretation of my writing. It looks fantastic, and I find a lot of the details well worth meditating on.

Consider the priest's hand.

Does this depict the gradual mechanization of humanity? Our dehumanization that is being wrought by late-stage capitalism as it consumes every part of human existence until there is nothing left? Is this act of communion one final prayer for God's help and salvation as humanity is snuffed out by the megamachine?

Or, does it depict a dramatic rescue for someone who's lost their hand? Is this technology one that is pro-human, because this priest may have been injured or ill? Perhaps this robot hand is the only way the communion chalice could even be lifted?

Or, is it both of these things?

I often write about the downsides of modern technology, but I'm equally sure it's important to remember the positives. I am not some kind of "Trad" who seeks to "go back" in order to flee from the ills of the present. Much technology is good. Much is bad. Sometimes the same thing is both. The difficulty in all this is in understanding the true gray area that shadows most of our relationship with it.

In addition, there are few secrets hidden in the image that won't make sense until (or, unless) a long-dormant sci-fi novel I've been writing is finished. So that will have to wait for another day.

But I wanted to draw attention to this image since I'm especially pleased with how it came out and I look forward to it gracing the site's home page for a long time.

I have more thoughts on the meaning and purpose of human "generated" art below, but, first, an announcement of sorts.

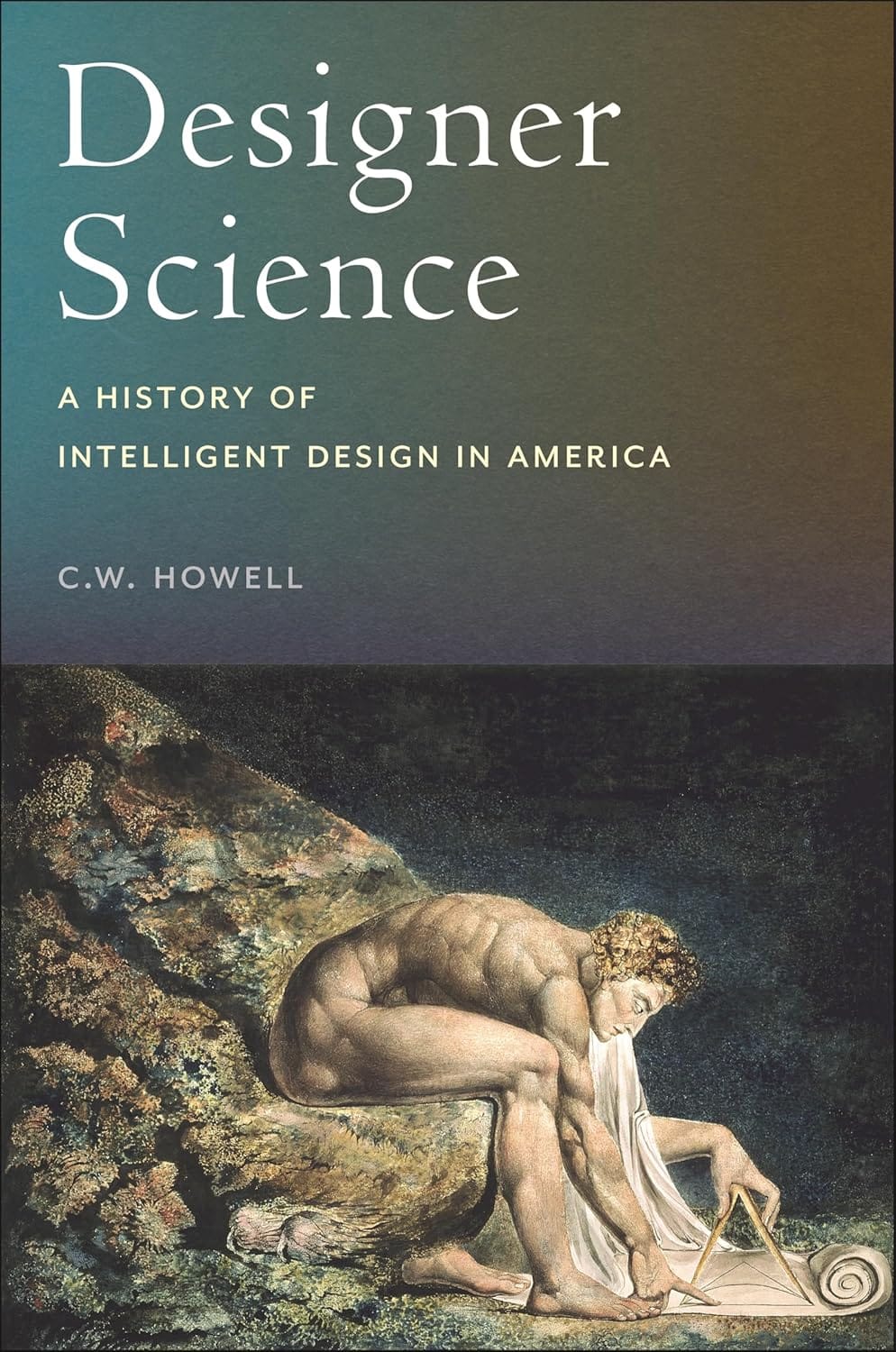

First Review of Designer Science

We're entering the home stretch now for my book's publication.

The release date is September 9, 2025, and it's fast approaching. To that end, I was fortunate to receive, in Publishers Weekly, my first review . I'll reprint it below:

Researcher Howell debuts with a fascinating survey of the intelligent design movement, a late 1980s through early 2000s effort to displace Darwinian evolutionary theory. Religious opponents have long argued against evolution, viewing the notion that life developed without direction from a creator as a repudiation of the Bible. Yet as efforts to debunk evolution failed to gain acceptance in public school classrooms, a group of anti-evolutionists decided to attack Darwinism via its roots in naturalism, or the belief that there is nothing beyond nature–a “strategic” attempt to dismantle evolutionary theory on philosophical rather than biblical grounds. Howell traces how the movement garnered support throughout the 1990s and early 2000s from the right, including conservative intellectuals and “grassroots evangelical populists” wielding intelligent design in “culture-war campaigns against US secularism.” By the mid-2000s the movement had faltered for reasons including the inability to produce a convincing alternative to Darwinism and was largely barred from classrooms. Still, Howell convincingly argues that intelligent design permanently influenced American conservative culture by casting the kind of doubt on “the reliability of scientific practice” that fueled later skepticism against vaccines and climate change. Deeply informed and substantive, this is a trenchant examination of the contested terrain where science, religion, and politics battle. (Sept.)

I am very gratified to have received a positive review for the book from an outlet as well-known as Publishers Weekly. They're anonymous, so I don't know who wrote it, but I appreciate their time and the review they put together.

More reviews are likely in the future, and I'll keep you all apprised as the release date draws closer.

Now, to return to your regularly scheduled program on art and machinery.

Thoughts on Art from a Century Ago

I recently read an almost century-old book called The Importance of Living by Lin Yutang, a curious figure in the history of American (and Chinese) Christianity.

Lin had an interesting life. He was born in China and was raised in a Christian family. His father was a Presbyterian minister, and he was given a missionary education of the type that was common in China during the late Qing and Republican eras of Chinese history. He later studied at Harvard and Leipzig and traveled the world, finally settling in the USA in 1935. One of his most unusual achievements is that he invented a workable Chinese typewriter (a difficult task considering Chinese uses characters and not letters for its script).

Over time, Lin became disenchanted with Christianity. He was especially angry that his countrymen were forced to pledge fealty to doctrines like the resurrection and virgin birth in order to be baptized, all while the western scholars and theologians he met abroad often didn't hold to these views themselves.

He turned back to the ancient wisdom of Chinese traditional religion and ethics and renounced Christianity. He wrote a chapter in The Importance of Living called "Why I Am A Pagan."

His wife, however, stayed Christian, and so did the rest of his family. And though he was defensive about Chinese culture and philosophy, he didn't remain a "pagan" forever. By the late 50s, he had returned to Christianity and even wrote a follow up book titled From Pagan to Christian.

Lin Yutang's books outline his religious evolution. The Importance of Living is from 1937 and From Pagan to Christian is from 1959.

I mention his unique life trajectory to give context to his thoughts on art and education from the 1930s. He was a very popular writer at the time, and he carved out a name for himself as one of those numerous writers who seek to impart "Eastern wisdom" to those of us in the spiritually desiccated west. But because Lin was an educated man with deep knowledge of both eastern and western philosophy, his view of these things was far more substantive than is usual in that rather banal subgenre.

It was from this mindset that he wrote The Importance of Living, his most famous book (still in print today), in which he argued against the frenetic pace of American life and its obsession with productivity, efficiency, and "getting things done." This was not, he felt, actually a good life, and had overlooked many of the most important things in living. That is, life itself.

Lin's writing on art and human creativity is especially pertinent.

Art, he thought, "is both creation and recreation."

It should not be thought of as the province of an elite or small sect of humanity. It is not just for the masters and their masterpieces, or the tortured geniuses and their legacy. It's a necessary part of everyone's human existence. "I think the spirit of true art can become more general and permeate society only when a lot of people are enjoying art as a pastime, without any hope of achieving immortality."

It's similar with sports. We play games because they are fun, not necessarily because they will give us money or fame (because that's only possible with 0.0001% of athletes).

This same spirit of play is needed in art.

Lin felt it was "more important that all children and all grown-ups should be able to create something of their own as their pastime than that the nation should produce a Rodin." It's the task of everyone. "I am for amateurism in all fields," he contended.

"It is only when the spirit of play is kept that art can escape being commercialized."

One of Lin's primary targets was advertising and propaganda (writing, as he was, during the rise of fascism in Europe). This militates against the free spirit of art, because such images are created only for the ends of sales or, even worse, loyalty to Dear Leader. "Freedom is the very soul of art," he wrote, "modern dictators are attempting the impossible when they try to produce a political art. They don't seem to realize that you cannot produce art by the force of the bayonet any more than you can buy real love from a prostitute."

I believe this same line of reasoning applies to AI-generated art.

Sure, it's all fun and games when you play around with prompts just to see what sort of wackiness will return to you. But that is the extent of whatever "play" is involved in such generations.

Sadly, we're seeing more and more efforts at normalizing AI-generated writing and images as somehow licit and legitimate expressions of human creativity. For just one such example, the novel-writing organization NaNoWriMo attempted to mainstream the usage of AI for "national novel writing month" in a truly despicable act of moral cowardice. Fortunately, there was enough of a backlash against this that NaNoWriMo deservedly collapsed afterward, but we'd be foolish if we think this kind of thing will end.

Lin's critique is apposite here. There is no "play" in AI-generated art. There is no heart to it. Amateur, after all, is related to the Latin word for love, and there is not real love in it either.

His words can easily be modified: you cannot produce art by force of the algorithm any more than you can buy real love from a prostitute.

I do hope we might see a return to the "Birth of the Author." It is a consummation devoutly to be wished. We've become accustomed in education and popular culture to separate the art from the artist and critique it on its own grounds, apart from the "intent" of the creator. This is all well and good, and is often necessary. I used Roland Barthe's "Death of the Author" essay in my classes many times, simply to disabuse my students of the notion that the only point of literary analysis is to guess what the author was thinking.

But in an AI age, we may need to once again prioritize the intention of the creator.

Even if an AI-generated image is virtually identical to one made by a human, it will lack this spirit of play, of love, of amateurism that constitutes real human experience. It will be superficially the same but it will have no internal substance.

As a thought experiment, think of a work of art that is made as a gift.

J.R.R. Tolkien first wrote The Hobbit as a present for his children. Does anyone truly think Christopher Tolkien would have loved that book as much as he did if, instead of knowing it was the product of his father's tireless study of language, his love for fairy tales, and his love for his own family, it was instead spit out by ChatGPT after Tolkien prompted it with "write a fairy-story for my son about a short, hairy-footed man who comes across a magic artifact"?

Even if the AI dribbled out of the corner of its mouth the exact word-for-word book as The Hobbit (perhaps in the manner of Pierre Menard rewriting "the Quixote" verbatim), it would have none of the spirit of magic and majesty that makes it one of the greatest children's books of all time. Christopher Tolkien would have had no reason to read it.

It's important to keep this perspective on art, because it's going to come under increasing attack in the future, especially once we collectively realize that AI-art is more "efficient" than human art.

As Lin reminds, though, sometimes the most human thing is to just leave something undone. Efficiency isn't the point. Regarding AI-generated images, that's probably for the best. Start something, even if you don't finish it--you've still accomplished something human: both creatively and recreatively. We're amateurs, not algorithms. To leave it undone is still to do it. To prompt it is to never start at all.

Member discussion