The God of this World: A Review of Kenogaia by David Bentley Hart

“In whom the god of this world hath blinded the minds of them which believe not, lest the light of the glorious gospel of Christ, who is the image of God, should shine unto them.” - 2 Corinthians 4:4

David Bentley Hart is one of the world’s most influential theologians at present. One can measure this just by the fact that his books are read outside the guild and get reviewed in major outlets like The New York Times or The Wall Street Journal.

But Hart has sometimes resisted being called a theologian. He was trained as a religious studies scholar, and his work covers a wide variety of topics outside theology proper. In fact, in an old interview at SLU, Hart said that studying theology happened mostly as an accident, and that he had wanted to be a novelist.

No surprise, then, that Hart has published some fiction. In 2012, he released a collection of short stories The Devil and Pierre Gernet. Reading it was an especially unique experience for me because one of the stories—“The Other”—was set in the neighborhood in Prague (near Národní Třída) in which I lived at the time, and I had passed by the street and hotel setting of the story many times over the year I lived there.

For years, this was the only fiction Hart sent out into the world, but lately there’ve been some unusual additions. First, I am ashamed to admit (in my first version of this post) that I didn't include Hart's two children's books—an especially egregious mistake, considering I once interviewed him on that very topic! The first, The Mystery of Castle MacGorilla, came out in 2017, and the second, The Mystery of the Green Star, was just recently published in late 2023. Both were co-written with his son, Patrick. I have not read Green Star yet, but I plan to soon. Hart has long been passionate about children's literature, as he explained to me and my colleague Amber Salladin when we talked to him.

A few years later, Hart returned with a somewhat fiction-adjacent book, Roland in Moonlight, a hybrid memoir, philosophical meditation, collection of poetry, and series of dialogues with Hart’s wise tutor, his dog Roland, was released to acclaim in 2021.

But the focus of this post will be on another 2021 release, the novel Kenogaia—subtitled rather ominously as “A Gnostic Tale.”

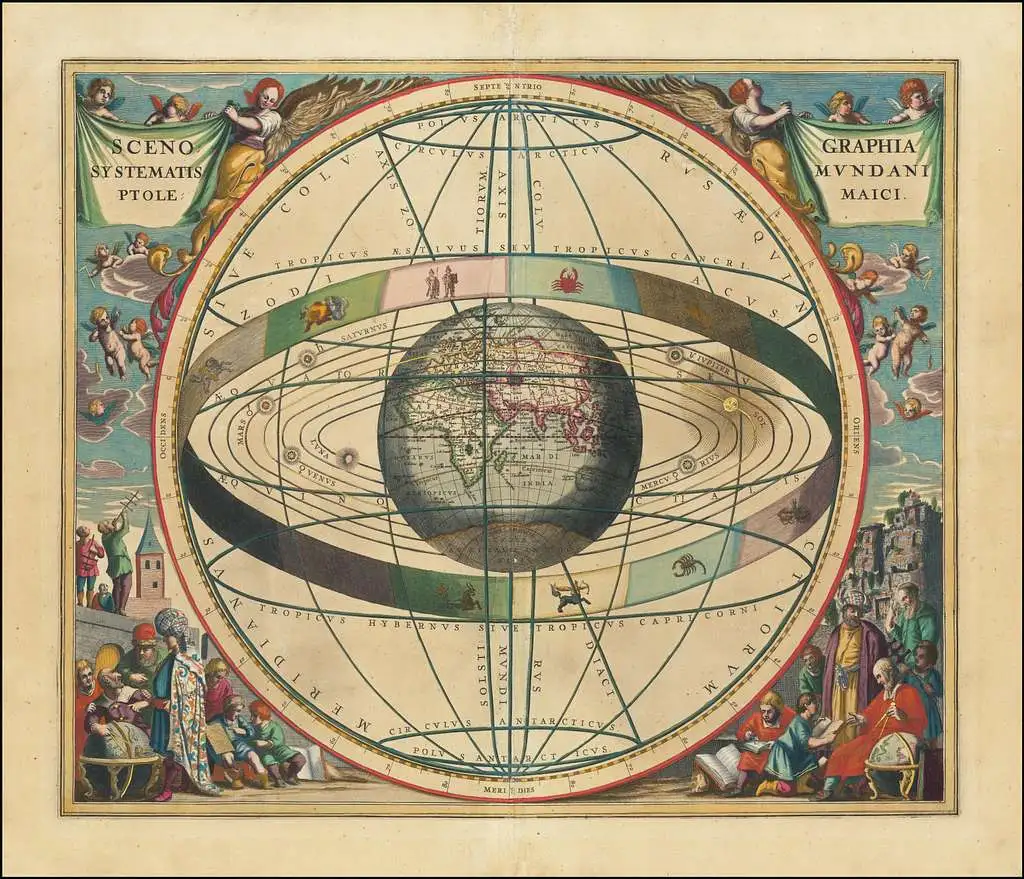

Kenogaia is something of a bildungsroman, set in an alternate reality—the planet Kenogaia—in which Ptolemaic astronomy, Enlightenment mechanical philosophy, and Gnostic cosmology all coexist. The world could plausibly be called steampunk, and it actually reminded me of Final Fantasy VII a bit—with its aerial barges, its blending of fantasy and technology, its corrupt megalopolis, and even its gathering of little magical balls (materia?) that the heroes use to fight evil.

The story follows one Michael Ambrosius, who, upon gazing through his father’s immense telescope, is initiated into knowledge of cosmological and astronomical truths that would upend the existing worldview of Kenogaia’s people. His father, who allowed but then regretted permitting Michael to see what he had discovered, is immediately arrested as a rogue disturber of the peace and Michael embarks, along with his friend Laura, on a quest to find him, in the process meeting a mysterious young emissary from the great beyond named Oriens.

Hart can be something of a controversialist at times, boldly challenging some of the supposedly received wisdom of Christian theology (the eternality of hell, as a most notable example) but I think that Kenogaia might be his most radical book. Not only does it playfully depict a more “Gnostic” version of the Christian story, it also repeatedly castigates the design argument and inveighs against Calvinist understandings of God.

A Gnostic Tale

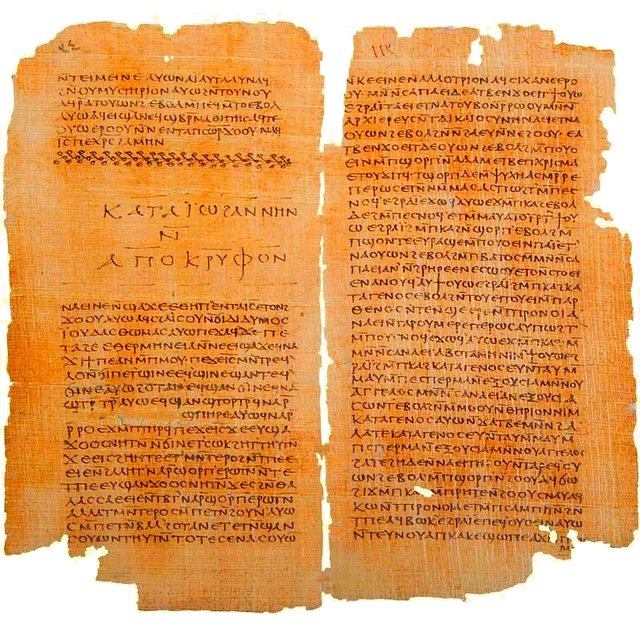

In his translation of the New Testament, Hart contended that we do not understand Gnosticism as well as we think we do. Or, rather, that the worldview and outlook of Gnosticism is not as alien to the early church (and especially some parts of the New Testament, like the Gospel of John) as we like to think.

Take, for example, this excerpt of the cosmology of the New Testament as Hart sees it, from his book Tradition and Apocalypse. Gird up your loins, it’s a bit of a long passage to reproduce here, but it’s worth reading in full:

In the New Testament, and most especially in the Pauline corpus and Fourth Gospel, no concern could be more crucial to the understanding of the redemption in Christ than a theology of the angelic archons and powers thronging the heavenly spheres above and separating this world from God’s highest heaven, or of the demons roving the earth, or of the kingdom of death below, or of the two ages of creation. Much of the New Testament narrative of salvation tells of a cosmic dispensation under the reign of the God of this aeon (2 Cor. 4:4) or the Archon of this cosmos (John 14:30; Eph. 2:2) or the “Evil One” (1 John 5:19), and of spiritual beings hopelessly immured within heavenly spheres occupied by armies of hostile archons and powers and principalities and daemons (e.g., Rom. 8:38-39; 1 Cor. 10:20-21; 15:24; Eph. 1.21), bound under and cursed by a law that was in fact ordained by lesser, merely angelic or archontic powers (Gal 3:10-11, 19-20). Into this prison of spirits, this darkness that knows nothing of the true light (John 1:5), a divine savior descends from the Aeon above (e.g., John 3:31; 8:23), bringing with him a wisdom that has been hidden from before the ages (Rom. 16:25-26; Gal 1:12; Eph. 3:3-9; Col. 1:26), a secret knowledge unknown even to “the archons of this cosmos” (1 Cor. 2:7-8) that has the power to liberate fallen spirits (e.g., John 8:31-32). Now those blessed persons who possess “gnosis” (1 Cor. 8:7; 13:2) constitute something of an exceptional company, “spiritual persons” (πνευματικοί), who enjoy a knowledge of the truth denied to the merely “psychical” or “animal” (ψυχικοί) among us (1 Cor. 2:14-15; 14:37; Gal 6:1; Jude 19). By his triumph over the cosmic archons, moreover, this savior has opened a pathway through the planetary spheres, the encompassing heavens, the armies of the air, and the potentates on high, so that now “neither death nor life nor angels nor Archons nor things present nor things imminent nor Powers nor height nor depth nor any other creature will be able to separate us from the love of God” (Rom. 8:38-39).

If this sounds vaguely Gnostic, then that is, for Hart, simply because the conceptual world of the Gnostics and the world of the early Christians was not so radically different as we believe now. There was a reason, after all, that so many were tempted to it, and that it was such a serious issue for the early Fathers to reckon with.

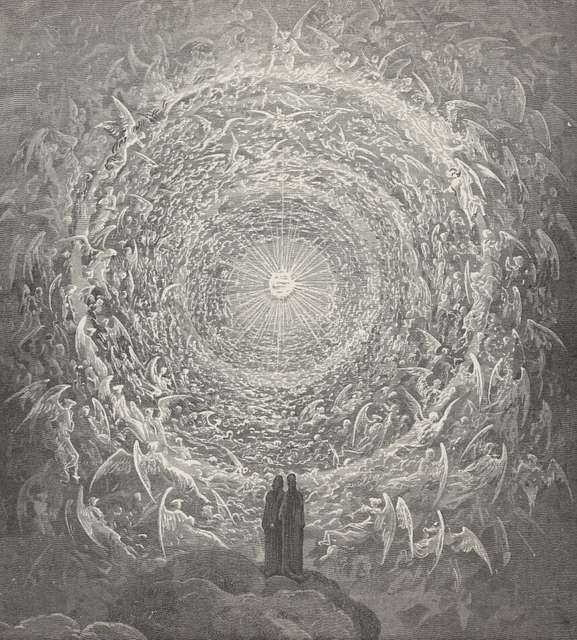

Moreover, this “plot” of the Gospel of John and the letters of Paul is also the plot of Kenogaia. The “empty world” of Kenogaia itself languishes in the thrall of a despotic and tyrannical god/archon, and Oriens—the emissary—comes from beyond the spheres to bring the new wisdom and secret knowledge to a select group of followers, people he has come to remind who they truly are.

The Great Artisan and the Grand Machine

The demiurgic deity who rules over Kenogaia is called the Great Artisan. Gnostic demiurge, yes—but he is also the God of natural theology. The chief method of knowing him is to study nature and deduce proofs of his power from its complex design (it is reminiscent of the Grand Architect from The Outer Worlds—a similarly deistic creator of the rational systems of the cosmos and capitalism, which I wrote about a few years ago).

There was an Age of Illumination in Kenogaia (what we call the Enlightenment in our world), and it taught the great truth of reality: that everything, the world, yourself, the whole cosm, is a machine.

This forms a bedrock part of Michael Ambrosius’s education—in school he must take a “history of design” class. Michael notes that his teacher was dismissive of the so-called “vegetal” arts. Such presumably organic understandings of the world must be resisted, for the whole proof of the Great Artisan’s existence hangs on artifice and complexity in nature.

(This is, though, always an assertion rather than a deduction—recall Hume’s complaint: if one’s main argument is “The world… resembles a machine, therefore it is a machine, therefore it arose from design,” then why can’t one also argue “The world…resembles an animal, therefore it is an animal, therefore it arose from generation”?).

Not just the natural world, but the psychological and cultural is likewise mechanized. Old books are appropriate only for the study of Social Pathology and Psychohistory (a dig at Isaac Asimov perhaps?). Stories are mechanical narratives, too, permissible only if written in the “industrial mechanistic realist” style. And last, but certainly not least, the economic system is grounded in this mechanistic metaphysics. As the psychologist Professor Tortus lectures Michael and Laura, “Our life—all life—is just an effect of the cunning arrangement of things that are essentially dead—matter, magnetism, random motions, what have you.” The Great Artisan’s glory is that he can make the dead particles appear to be living machines. Capitalism, too, cannot exist without this worldview, and “It’s only because men are driven by rational self-interest to acquire all they possibly can that the great machine of wealth-creation can function.”

Such musings form the basis of Kenogaia’s religion. At one point, Mr. Lucius, one of the lupine antagonists in the novel, rhapsodically hymns about “the great machine of earth and sky,” and how everything is

So exquisitely calibrated in all its parts: all its springs and levers, gears and pistons; all that shines and sparkles, and glitters and glints. Know thyself, who art the most superb machine of all, to be a veritable mirror and epitome and microcosm of the whole…. See how everything declares the power, providence, and pride of the Great Artisan…

The whole system is a fabulous and fragile conglomeration of constitutive parts arranged just so. It is, in a phrase, “irreducibly complex.”

You might recognize this concept from the intelligent design movement. I’m currently revising my manuscript on the history of ID, and so I could not help but notice the design language in Kenogaia. Furthermore, it is not the first time that Hart has linked the demiurge to the deistic designer. As he wrote in The Experience of God, “The recent Intelligent Design movement represents the demiurge’s boldest adventure in some considerable time.”

The question that always dogged ID (and design arguments as a whole) is who is this designer?

William Paley is one of the most famous figures associated with the design argument—with his classic scenario of finding a watch in a ditch and correctly deducing that a creator must have made it. It assumes a mechanical understanding of nature-as-contrivance. The eye is like a telescope, a telescope is a machine, a machine must be designed, etc. The biochemist Michael Behe coined the aforementioned term “irreducible complexity,” and he meant it as a biomechanical attack on neo-Darwinism, arguing that (say, a bacterial flagellum or an eye) was composed of such interlocking and mutually necessary parts that the removal of one would cause the entire system to cease functioning—meaning, then, that they could not have evolved gradually without guidance.

Behe has been open about equating life to machinery. All of ID uses mechanical language, but its advocates are not always so blasé about making the analogy a statement of fact. But Behe is. For him, molecular biology is machine biology. As he wrote in reply to his colleagues Gregory Lang and Amber Rice, “‘molecular machine’ is no metaphor; it is an accurate description. Unless Lang and Rice are arguing obliquely for some sort of vitalism—where the matter of life is somehow different from nonliving matter—then of course proteins and systems such as the bacterial flagellum are machinery. What else could they be?”

Design arguments only get you so far, though. Paley tried to extrapolate from nature to start doing theology, to try to understand who God was and what his attributes were. He concluded omnipotence and benevolence. The latter is where problems might start to arise.

After all, nature can be beautiful—but it can be violent, vicious, and frightening. Darwin lost his faith less because of science than he did because of the horrible cruelty of nature. Before publishing On the Origin of Species, Darwin wrote to a friend, “What a book a devil's chaplain might write on the clumsy, wasteful, blundering low and horridly cruel works of nature!"

This means that natural theology (and, to an extent, ID—though it often resists going as far as natural theology) is highly susceptible to the problem of evil. Whereas Paley and Gottfried Liebniz might soliloquize about how happy the world is, and how it is the greatest possible reality, those in the throes of suffering are not likely to agree.

And what of the imperfections of nature? The so-called “bad designs”? Like the human back or laryngeal nerve? The panda’s thumb? What does that say about the character of the creator? It is here that theology extrapolated from nature begins to seriously struggle. You end up, as in Kenogaia, realizing that the world is maybe not made all that well. In Kenogaia, it’s a toy, it has flaws. There’s broken and cracked gears in the great wheeling spheres. It is a clockwork universe that can break down.

So—what is the character of this designer? This is where Kenogaia pushes to its radical edge. In the story, the designer is not a god worthy of worship but a diabolical villain.

The Devil's (Chaplain) in the Details

It is not the self-existent creator of the cosmos who is worshiped on Kenogaia. Not, that is, the classic understanding of God. Instead, they are under the oppressive rule of “the God of this world”—the capricious and cruel Lord Theoplast, a sorcerer from the Pleroma (the full world) who created the great machine as his plaything and pastime. He kidnapped Oriens’ sister, Aurora, and weaves the world from her dreams. He made war on the Pleroma with his machines. In a kind of diabolic inversion of Narnia’s heaven, the oneirological Kenoma he forged is bigger (and emptier) on the inside than the outside.

He refers to himself as “the god of this world” and demands reverence and fealty. This is, of course, the title Paul gives not to the Creator but to the Adversary. “I have seen too much of this machine,” Oriens says, and calls Theoplast a monster. “The maker of this world is unspeakably cruel,” he shudders at a particularly dark point of the novel.

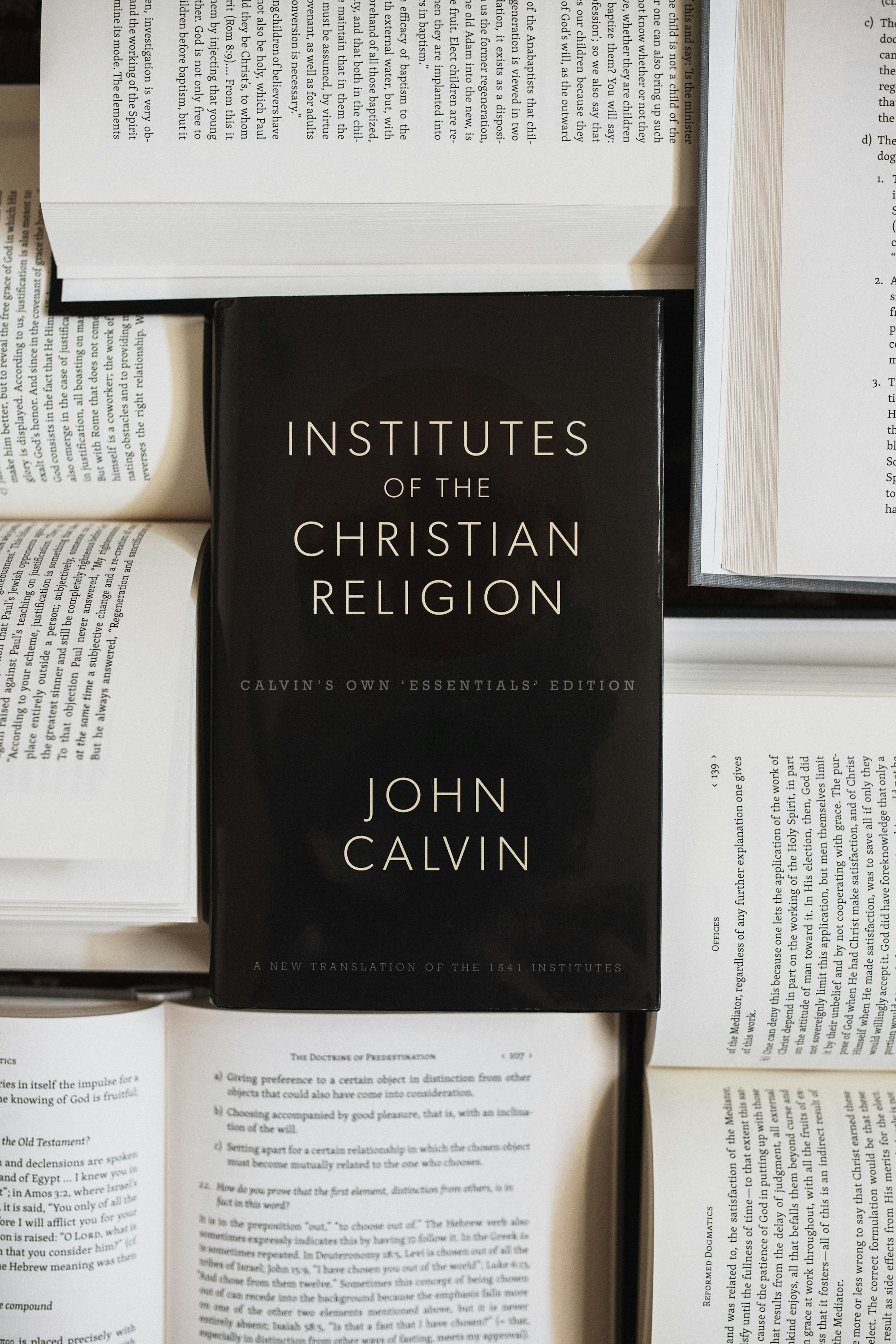

Not only, however, does Kenogaia depict the God of natural theology as the Gnostic demiurge; Hart also links this devilish deity with the God of Calvinism. The way Lord Theoplast demands total obedience, threatens eternal hellfire, elects and unelects those at will. As Michael relates being taught at school, “The Book of Disciplines says that the Great Artisan created [hell] to reveal his love and justice.” Oriens is aghast, “Love and justice?....That makes no sense.”

Even Lord Theoplast’s name seems telling here—possibly a portmanteau of theology and neoplasm?

If there is one form of Christian theology that is cancerous, for Hart, it is Calvinism (though it has close competition from two-tier Thomism). Hart has never shied away from criticizing Calvin, but what makes Kenogaia distinct is the way it fuses Calvin, natural theology, and the Gnostic demiurge into one villainous unity that must be resisted.

But, as Hart is keen to contend, the Gnostics, in recognizing the bungling nature of nature, and in understanding the cosmos as under the dominion of a rogue archon, were closer to Christian thinking than modern theology often is. Hence, in Tradition and Apocalypse, he writes that the arch-Gnostic Valentinus possessed an “understanding of salvation” that was not as “remote from Paul’s, in either shape or substance, than was Calvin’s tragically misguided theology of substitutionary atonement.”

Certainly any Calvinist would dispute this, and perhaps find it unduly harsh. But Hart is not alone or even that unusual in such a line of thinking. I was surprised, recently, to find that C.S. Lewis (that most urbane of Christian writers) made similar observations in his English Literature in the Sixteenth Century (that book will be the subject of my next post).

In writing of the theology of the sixteenth century, Lewis took care to note that the primary expression of Reformed and especially Calvinist rhetoric was devotional and experiential. That is, it was somewhat romantic—the ecstatic devotion of the unworthy lover for the glorious beloved. It is the kind of sentiment that informs the songs of troubadours and love stories today. It focuses on how perfect and unblemished the object of love is, and how worthless and incomplete is the love offered by fallen beings like us. And yet, glory of all glories, it is enough, and so the devotional piety of Reformed thinking was primarily positive and affirming, even joyous, the same way a love song might be. No dark, dour, Puritan pessimism (a mischaracterization anyway) here.

But, Lewis writes, that all changes when Calvinist thinking is transformed from an emotional experience of salvation into a systematic theology. He contends, “Propositions originally framed with the sole purpose of praising the Divine compassion as boundless, hardly credible, and utterly gratuitous, build up, when extrapolated and systematized, into something that sounds not unlike devil-worship.”

For Lewis, much of this owed to Calvin’s personality. He was “a man born to be the idol of the revolutionary intellectuals: an unhesitating doctrinaire, ruthless and efficient in putting his doctrine into practice.” And in guiding the intellectual development of Protestantism, “Calvin goes on from the original Protestant experience to build a system, to extrapolate, to raise all the dark questions and give without flinching the dark answers.” The culmination of this is that Calvinism seems to take up a view of power “which comes near to saying that omnipotence must be worshiped even if it is evil.” It would be hard to summarize Kenogaia better.

And, to take it back to natural theology, if the only attribute of the designer that can really be extrapolated from nature is power—omnipotence—is that enough to build a religion? Or might it, as Lewis observes, suggest dark questions that can lead to even darker answers?

Revelation

The recourse is to look to revelation itself. The weakness of natural theology, of the design argument, is that it cannot draw on revealed tradition. And what does the story say?

This is, I think, what Hart is doing with Oriens in Kenogaia. The irruption of light into the dark, empty world, to reveal what is true but what cannot necessarily be known from nature or experience.

We see, in Oriens’s mission to rescue his lost sister Aurora, the Christian theology Hart has outlined frequently in his nonfiction: the boundless love and compassion for humanity, the willingness to go through whatever is needed to rescue those who are trapped in the prison of darkness, even should it mean descending into hell to do so, and the eventual leading and achieving of a universal restoration of all in the apokatastasis of the novel’s conclusion, which suggests (but does not show) that even Lord Theoplast might not be without possible redemption.

Perhaps it all sounds non-traditional. But as Hart pointed out in Tradition and Apocalypse, tradition must be a kind of unveiling, a future-oriented apocalypse, and not hidebound fidelity to the confusions and incompatibilities of the past or present. When we are unsure whether something should be defined as heretical or not, our only foolproof method to find heresy is “in cases of moral departure from the explicit teachings of Christ.” And if our natural theology and our systematics encourage just such a moral departure…well, then…?

Kenogaia is possibly Hart’s most provocative book, for all the reasons outlined above. But it also is a complete encapsulation his thought and approach to theology. And, really, speaking as someone who was definitively nurtured in the study of religion by C.S. Lewis, I suspect any theology worth taking seriously must also be able to find expression in fiction, just as Hart's has here.

*An earlier version of this piece contained the typo Plenoma instead of Pleroma, and also left out two of Hart's most important books.

Member discussion